This street, created in 1919 by Ordinance 39638, is named for W Marginal Way SW. It begins there and goes just under 800 feet northwest to a dead end underneath the West Seattle Bridge. The Duwamish Trail continues on from there to the West Seattle Bridge Trail, while the 18th Avenue SW stairway heads south up the hill to SW Charlestown Street in Pigeon Point.

Tag: Water

E Superior Street

This street, along with E Huron Street and Erie Avenue, was created in 1890 as part of Yesler’s Third Addition to the City of Seattle. It was named for Lake Superior, the largest of the Great Lakes, and the largest freshwater lake in the world by surface area.

E Superior Street begins at Euclid Avenue and goes 1⁄10 of a mile east to Erie Avenue.

E Huron Street

This street, along with E Superior Street and Erie Avenue, was created in 1890 as part of Yesler’s Third Addition to the City of Seattle. It was named for Lake Huron, second largest of the Great Lakes by surface area.

E Huron Street begins at Euclid Avenue and goes 1⁄10 of a mile east to Lake Washington Boulevard.

Erie Avenue

This street, along with E Superior Street and E Huron Street, was created in 1890 as part of Yesler’s Third Addition to the City of Seattle. It was named for Lake Erie, fourth largest of the Great Lakes by surface area.

Erie Avenue begins at Leschi Park south of Lake Washington boulevard and goes ⅓ of a mile north to E Jefferson Street.

Elliott Avenue

Elliott Avenue, which originated as Water Street in A.A. Denny’s 6th Addition to the City of Seattle, filed in 1873, received its current name in 1895 as part of the Great Renaming. It was named for Elliott Bay, which was itself named for Midshipman Samuel Bonnyman Elliott (1822–1876), part of the United States Exploring Expedition, otherwise known as the Wilkes Expedition. (Even though for years people thought the bay had been named for Chaplain J.L. Elliott, Howard Hanson makes a convincing argument in “The Naming of Elliott Bay: Shall We Honor the Chaplain or the Midshipman?”, an article in the January 1954 issue of The Pacific Northwest Quarterly, that the honor belongs to the midshipman.)

Elliott Avenue begins at Western Avenue and Lenora Street and goes 2⅕ miles northwest to halfway between W Galer Street and W Garfield Street, where it becomes 15th Avenue W.

Looking south down Elliott Avenue W at W Mercer Place, August 1921. Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Identifier 1862

Looking northwest up Elliott Avenue W from the W Thomas Street pedestrian bridge, August 2015. Photograph by Dllu, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Montlake Boulevard E

This street originated as University Boulevard. Opening on June 1, 1909, it connected Washington Park Boulevard (now E Lake Washington Boulevard) to the entrance to the Alaska–Yukon–Pacific Exposition (now the campus of the University of Washington). The plan was for it to continue through campus and connect via 17th Avenue NE to Ravenna Boulevard, but this was not done due to opposition from the Board of Regents. Instead, the road was extended along what was then Union Bay shoreline to NE 45th Street. It has been part of the state highway system since 1937.

Montlake Boulevard was named after Montlake Park, an Addition to the City of Seattle, filed in 1908, which later gave its name to the entire neighborhood. Most of the street, however, is on the other side of the Lake Washington Ship Canal.

Montlake Park ad, Seattle P-I, January 1, 1911. “Both the Cascade and Olympic range of mountains are within the range of vision, and every lot has an equal and forever unobstructible view of one of the lakes [Lake Union and Lake Washington]. Hence the name, ‘MONT-LAKE.’” Today, Montlake Boulevard E (as well as Washington State Route 513) begins at the intersection of E Lake Washington Boulevard and E Montlake Place E, just south of the Washington State Route 520 freeway, and goes 1⅓ miles north, then northeast, to NE 45th Street, just south of University Village. It becomes Montlake Boulevard NE as it crosses the Montlake Cut of the Lake Washington Ship Canal. (State Route 513 continues for another 2 miles along NE 45th Street and Sand Point Way NE, ending at NE 65th Street just west of Magnuson Park.)

Montlake Bridge, looking southbound, August 2021. The bridge opened in 1925 and is the easternmost bridge over the Lake Washington Ship Canal. Photograph by Flickr user Seattle Department of Transportation, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 2.0 Generic

Street sign at corner of E Montlake Place E, E Lake Washington Boulevard, and Montlake Boulevard E. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff, August 24, 2009. Copyright © 2009 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved.

West Montlake Park, January 2013. The body of water is Portage Bay (Lake Union); South Campus of the University of Washington is at right, across the Montlake Cut, and the University Bridge and Ship Canal Bridge are visible in the distance. Photograph by Orange Suede Sofa, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Puget Boulevard SW

Puget Boulevard is a curious street, for a number of reasons:

- The paved portions are only a few blocks long — hardly comparable to, say, Lake Washington Boulevard or Magnolia Boulevard;

- Both east–west and north–south portions are called Puget Boulevard SW, contrary to the rule that directional designations precede street names for east–west streets (this is why Lake Washington Boulevard E becomes E Lake Washington Boulevard when it curves west on its approach to Montlake Boulevard E);

- Despite its name, it has no view of Puget Sound, sitting as it does in the Longfellow Creek valley in the Delridge neighborhood of West Seattle;

- And, as it turns out, it isn’t even named for Puget Sound, as might be expected, but rather for the Puget Mill Company (later part of Pope & Talbot and today part of Rayonier).

The Puget Mill Company, which once owned large swaths of land in the city (including what became the Washington Park Arboretum and the Broadmoor Golf Club), made two donations to the city in 1912, according to the Ninth Annual Report of the Board of Park Commissioners:

- “A rugged tract of logged-off land south of Pigeon Point and Youngstown in the large unplatted area” (20.5 acres — this became Puget Park); and

- “A strip of land 160 feet in width extending from Sixteenth Avenue Southwest and Edmonds Street (sic) to Thirty-fifth Avenue Southwest and Genessee Street, a distance of 8,500 feet, and comprising an area of about fifteen acres for parkway purposes. Under the conditions of this gift improvement work must be undertaken within five years. This acquisition forms an important link in the contemplated boulevard to West Seattle.”

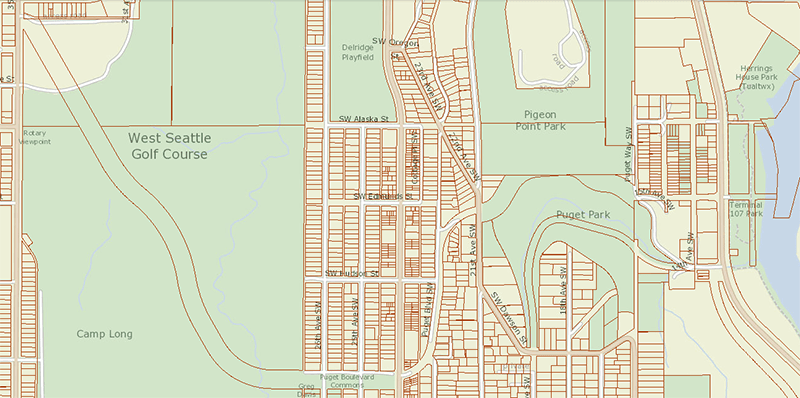

This strip is today’s Puget Boulevard SW. Two things become apparent when looking at the King County Parcel Viewer map of West Seattle:

- Almost the entire right-of-way still exists;

- But less than ½ a mile of it is improved; most of it runs through Puget Park, the West Seattle Golf Course, and West Seattle Stadium.

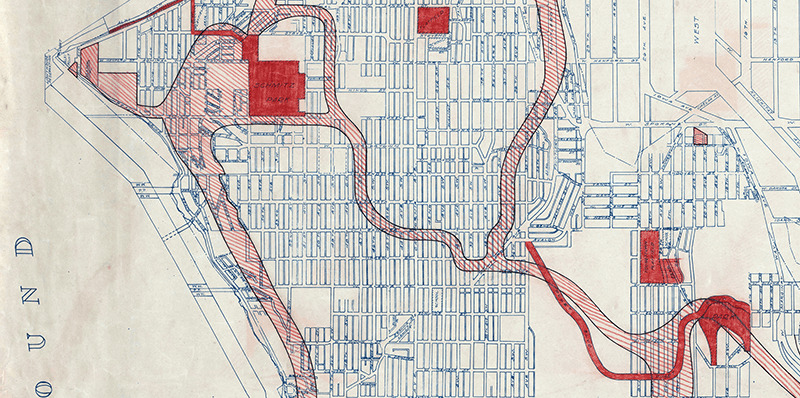

Map of Puget Boulevard, from King County Parcel Viewer Once past the present site of West Seattle Stadium, the “contemplated boulevard to West Seattle” was to have run, as the Friends of Seattle’s Olmsted Parks puts it,

[Across] California Avenue a few blocks north of [the] present-day Alaska Junction, at that time part of the “Boston Subdivision.” It would have then headed northwest and down a ravine, eventually turning southwest to terminate at Alki Point.

Map of proposed West Seattle Parkway, cropped from a 1928 map showing both existing (red) and proposed (red hatched) park features. Puget Park and Boulevard are at lower right. Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Identifier 2333. Returning to the question of the name — the Puget Mill Company was, of course, named after Puget Sound, which itself was named in 1792 by Captain George Vancouver of HMS Discovery for Lieutenant Peter Puget (1765–1822).

Today, the paved portion of Puget Boulevard SW begins at 23rd Avenue SW, about 1⁄10 of a mile north of SW Hudson Street, and goes ⅕ of a mile south to a dead end. After a very short section — not more than 150 feet long — east of Delridge Way SW, which serves as a driveway for a complex of townhouses, it resumes west of a foot path off Delridge and goes about 1⁄10 of a mile west to 26th Avenue SW. Along this stretch, there are houses to the north and the Delridge P-Patch and Puget Boulevard Commons to the south.

Beach Drive SW

Like Harbor Avenue SW, Beach Drive SW was once part of Alki Avenue SW. It became Beach Drive sometime between 1912 and 1920. In contrast to Alki and Harbor Avenues, most of Beach Drive’s beaches are private, though there is a long public stretch at the Emma Schmitz Memorial Outlook, as well as Lowman Beach Park at the south end.

Puget Sound shore looking northwest along Beach Drive toward Alki Point, August 2007. Photograph by Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported Beach Drive SW begins at Alki Avenue SW just south of Alki Point and goes just over 3 miles southeast to Trail #1 at Lincoln Park.

Signs along Beach Drive SW a little under 1,000 feet north of Lincoln Park. The park boundary sign is unofficial. Its placement appears to imply that the tail end of Beach Drive is private, which it’s not. Nor is the driveway (SW Othello Street) on the left. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff, March 10, 2013. Copyright © 2013 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved. Harbor Avenue SW

As noted in Alaskan Way, Harbor Avenue SW was once part of Railroad Avenue. When the Elliott Bay tidelands were platted in 1895, Railroad Avenue stretched from (using current landmarks) the Magnolia Bridge along the waterfront to the Industrial District, then across Harbor Island to West Seattle, ending southwest of Duwamish Head. In 1907 the West Seattle portion was renamed Alki Avenue, and sometime between 1912 and 1920 it was given its current name.

Looking northwest up what is now Harbor Avenue SW toward Duwamish Head, April 1902 Today, Harbor Avenue SW begins at SW Avalon Way and SW Spokane Street at the west end of the West Seattle Bridge and goes 1¾ miles northwest to Duwamish Head, where it becomes Alki Avenue SW.

Street sign at corner of Harbor Avenue SW and Alki Avenue SW, Duwamish Head, with Elliott Bay and downtown Seattle in background, October 2017. Photograph by Ron Clausen, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International NE Pacific Street

What is now Pacific Street was Harrison Avenue in the 1889 Latona Addition and Railroad Avenue in the 1890 Brooklyn Addition, corresponding to the eastern part of Northlake and to the University District, respectively. The road was built on either side of railroad tracks that were originally part of the independent Seattle, Lake Shore and Eastern Railway, but which were soon thereafter taken over by the Northern Pacific Railway. (The route of the SLS&E through and east of Seattle is now the Burke–Gilman Trail, the Sammamish River Trail, and the East Lake Sammamish Trail.)

In 1906, Harrison Avenue became Pacific Place and Railroad Avenue became Brintnall Place. (Why the opportunity wasn’t taken to match the names is unclear. Brintnall Place may have been named for Burgess W. Brintnall, who, according to the September 1912 issue of the Northwest Journal of Education, had been school superintendent for Olympia and Thurston County, founded the journal itself, and, after moving to Seattle in 1899, founded the Pacific Teachers Agency. He was murdered on July 3, 1912.)

At some point both streets became Pacific Street. Brintnall Place appears for the last time in The Seattle Times in October 1920, and Pacific Street for the first time in July 1921. The 1920 Kroll atlas shows all three names, including Pacific Place, indicating the change must have been planned at the time of its publication.

I haven’t seen any indication of why the Pacific name was chosen. Seattle got an Atlantic Street in 1895 — maybe it was thought the other major ocean deserved a street as well. But I wonder if it wasn’t named for the Northern Pacific, whose tracks the street ran along?

Street sign where NE Pacific Street becomes N Pacific Street on crossing 1st Avenue NE, August 2011. Photograph by Flickr user Panegyrics of Granovetter (Sarah C. Murray), licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Today, NE Pacific Street begins at Montlake Boulevard NE, at the north end of the Montlake Bridge and the southeastern corner of the University of Washington campus, and goes ¾ of a mile to Eastlake Place NE, underneath the University Bridge, where it becomes NE Northlake Way. It begins again at NE 40th Street just west of the Ship Canal Bridge and goes another ¾ of a mile to N 34th Street just east of Meridian Avenue N.

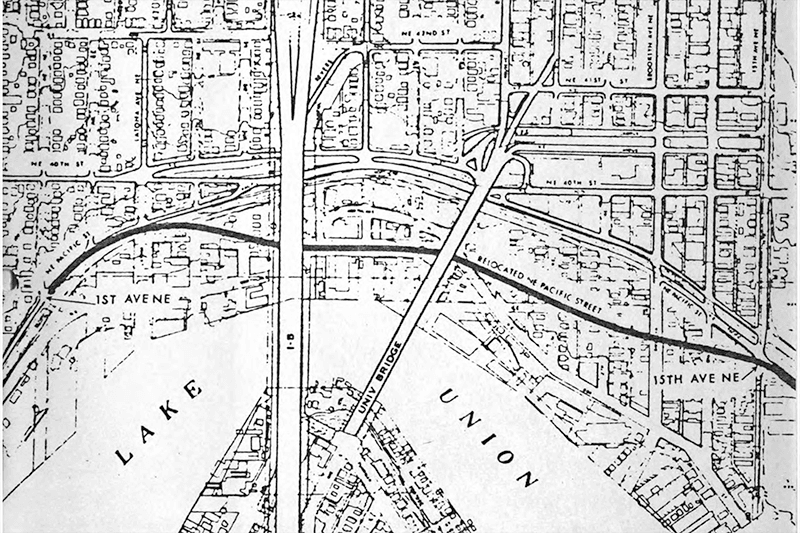

Pacific Street’s current configuration is the result of a realignment that took place in the 1970s; originally, instead of turning west at University Way NE, it kept going northwest, cutting through what is now the University of Washington’s West Campus, and there was no interruption between the University and Ship Canal Bridges. The Burke–Gilman Trail follows the original railroad alignment, though, as does, for a few blocks, the campus road Cowlitz Road NE.

Map showing proposed realignment of NE Pacific Street, from Draft Environmental Impact Statement for the Relocation of Northeast Pacific Street from 1st Avenue Northeast to 600 feet southeasterly of 15th Avenue Northeast in Seattle, Washington N Canal Street

This street appears to have been built sometime between 1908 and 1912. (It was established by ordinance in 1906, but that was legislation, not construction. [It was also originally named Ewing Street, the original name of N 34th Street, which still exists on the Queen Anne side of the Ship Canal.]) When the plat of Denny & Hoyt’s Addition to the City of Seattle, W.T., was filed in 1888, no such street was needed, because there was no canal. Instead, Ross Creek connected Lake Union to Salmon Bay. However, as work on the Lake Washington Ship Canal progressed, the Fremont Cut came into being, and it must have been felt a street paralleling the canal to the north was needed, since the original plat took no notice of the creek or any future canal route. (One to the south was needed, too, which is why Nickerson Street was extended from 3rd Avenue W to 4th Avenue N, at the southern end of the Fremont Bridge.)

Why, then, is Canal Street so short — not quite ⅓ of a mile from N 34th Street and Phinney Avenue N in the east to 2nd Avenue NW in the west?

As it turns out, even though Canal Street was to run to what was then the boundary between the cities of Seattle and Ballard at 8th Avenue NW, shortly after Seattle annexed Ballard in 1907 another street was laid out parallel to the canal connecting Fremont to the new neighborhood of Ballard: Leary Way NW (then simply Leary Avenue, all the way from Market Street to Fremont Avenue). Leary became the main arterial, and in 1951 NW Canal Street was vacated between 3rd Avenue NW and 8th Avenue NW, reducing it to its present length. (Until 2016, there was a slight discontinuity in the vicinity of 1st Avenue NW and N 35th Street where the built street deviated from its right-of-way, making it even shorter.)

So this isn’t quite the same as our trio of S Front Street, S River Street, and S Riverside Drive literally being cut short by the rechanneling of the Duwamish River into the Duwamish Waterway — more one of Canal Street being supplanted by Leary Way and becoming more valuable to the city as industrial land than as roadway.

S Riverside Drive

As you might expect, this street is so named because it runs along the west bank of the Duwamish Waterway. However, it only does so for about ⅖ of a mile, from S Webster Street east of 5th Avenue S to a dead end on the river just north of a path to t̓ałt̓ałucid Park and Shoreline Habitat (formerly the 8th Avenue S street end, just north of S Portland Street). It is by no means a prominent street, contrary to what such a name usually implies (Los Angeles, Manhattan, Ottawa, Spokane). In this way it is similar to Seattle’s S Front Street and S River Street. Why is this?

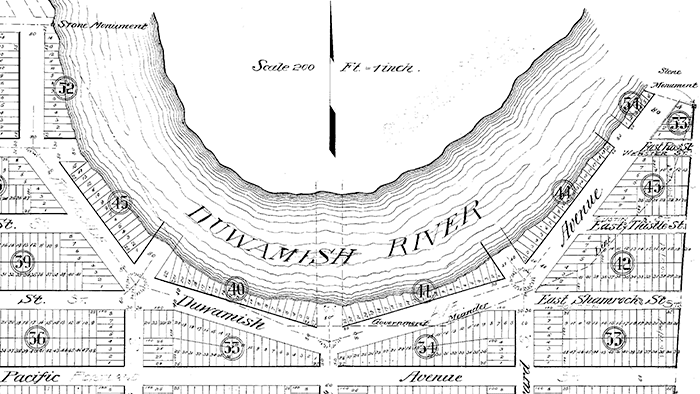

Also as you might expect, it’s for the same reason Front and River Streets are relatively unimportant: the rechanneling of the Duwamish River that started in 1913. Originally Duwamish Avenue in the 1891 plat of River Park, as seen in the image below, Riverside Drive used to curve around a bend in the river. When the river was straightened, the road was cut off right in the middle and became a Riverside Drive to nowhere.

Portion of River Park addition showing Duwamish Avenue (now Riverside Drive)

Signs at corner of S Holden Street, S Riverside Drive, and 7th Avenue S, May 20, 2013. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff. Copyright © 2013 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved. Lake Shore Boulevard NE

This street, created in 1906 as part of the Lake Shore View Addition to Seattle, begins in the north at NE 105th Street and Exeter Avenue NE, and curves south for a mile along the Burke-Gilman Trail, which parallels the Lake Washington shoreline, to a dead end at the north boundary of Matthews Beach Park. Unlike most, though not all, boulevards in Seattle, this one is not one of the Olmsted boulevards designed by John Charles Olmsted in 1903.

Riviera Place NE

This narrow street, created in 1926 as part of Riviera Beach, an Addition to King County, Washington, Divisions № 1, 2, 3, and 4, and situated between the shoreline of Lake Washington and the right-of-way of the Northern Pacific Railway, appears on the plats simply as “Road” — it first appears in The Seattle Times on July 20, 1930, as “Riviera Beach Road,” and then on July 2, 1932, with its current name. The name simply means ‘coastline’ in Italian.

Today, Riviera Place NE begins at the north city limits, where Seattle meets Lake Forest Park at the NE 145th Street right-of-way, and goes nearly a mile south along the Lake Washington shoreline to a spot a few houses north of NE 125th Street, where it ends at one house and picks up again on the other side of its neighbor. From there, it runs 1¼ miles south to its end at Lake Shore Boulevard NE between NE 100th Street and NE 103rd Street. The portions between the NE 135th Street right-of-way and NE 125th Street are private.

Riviera Place NE is probably most notable to the city at large for being the location of the NE 130th Street End park, which became an official park in 2019 after years of controversy. It’s not, strictly speaking, a shoreline street end, because it’s owned by Seattle Parks and Recreation, rather than being a right-of-way under the jurisdiction of the Seattle Department of Transportation. This is because it was never properly dedicated to the public in 1932 (see background and court filings). For years, it had been treated as just another shoreline street end, but in 2012, when the city announced its intention to make improvements to the beach to improve public access, the neighbors on either side filed suit, and ended up having their ownership of the lot confirmed. The city ended up having to exercise its right of eminent domain, condemned the property, and paid the neighbors $400,000 each. (As unfortunate as it was to have to pay $800,000 for the street end, I’d say it was worth it, as NE 130th is the only accessible shoreline street end north of NE 43rd Street, and the only public lake access, period, north of Matthews Beach [around where NE 95th Street would be if it had been platted into the water].)

View of NE 130th Street End park on Lake Washington east of Riviera Place NE, June 18, 2019. Photograph by Flickr user Seattle Parks and Recreation, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic NW North Beach Drive

This short street runs just over 750 feet from Triton Drive NW in the west to NE 98th Street in the east, just west of 24th Avenue NW. It was established in 1926 as part of North Beach, an Addition to the City of Seattle; at the time, it extended farther south, but that section is now 26th Avenue NW. The beach being referred to is on Puget Sound, across the BNSF Railway tracks from what is now NW Esplanade.

Although it bears the neighborhood’s name, houses along North Beach Drive are actually only eligible for associate, not full, membership in the North Beach Club, as the community boundary map shows. This is because the club, which originated in 1927 as the Golden View Improvement Club, was formed by and for residents of the Golden View and Golden View Division № 2 subdivisions, platted in 1924 and 1926, respectively. (According to state records, the GVIC was administratively dissolved in 1982 and merged into the North Beach Club [founded 1990] in 2006. [No word on what entity managed affairs from 1982 to 1990.]) In 1930, the club took over responsibility for the subdivisions’ water system from the developer, who as part of the deal deeded 1,500 feet of Puget Sound beach to the organization. It is this private beach, accessible via a short path from NW Esplanade at 28th Avenue NW, that is the North Beach Club’s primary raison d’être today, the water system having been hooked into the city supply long ago. Today’s associate members are the “descendants” of those who were interested in the Golden View additions’ water system 91 years ago but lived outside the subdivision boundaries — including residents of NW North Beach Drive.

NE Windermere Road

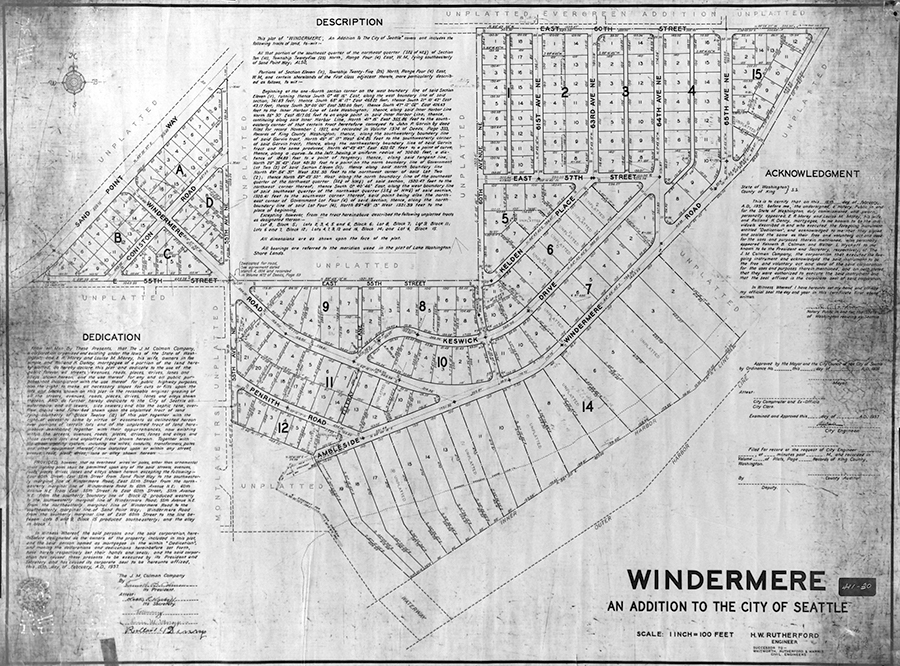

This semicircular street in Seattle’s Windermere neighborhood runs just over a mile from Sand Point Way NE between NE 55th Street and NE 58th Street in the west to just north of NE 61st Street in the east, at the southern end of Magnuson Park. The street and neighborhood itself were named after Windermere, the largest lake in England.

Plat of Windermere, an Addition to the City of Seattle, 1937. Courtesy of the Seattle Municipal Archives, Identifier 1628. Windermere was developed in the late 1920s by Laurence James Colman (1859–1935) and his son, Kenneth Burwell Colman (1896–1982). Their J.M. Colman Company, founded by Laurence and his brother, George Arnot Colman (1861–1933), was named for Laurence and George’s father, James Murray Colman (1832–1906), namesake of Colman Dock and the Colman Building. (Colman Pool was established by Kenneth and named after Laurence.)

Unfortunately, as with far too many Seattle subdivisions, Windermere deeds came with racial restrictive covenants. The relevant part of this deed reads as follows:

Said property shall not be conveyed, sold, rented, or otherwise disposed of, in whole or in part, to, or be occupied by, any person or persons except of a white and Gentile race, except, however, in the case of a servant actually employed by the lawful owner or occupant thereof.

Notably, although membership in the Windermere Corporation does come with access to the private Windermere Park and Beach Club, all streets in the neighborhood are public — it is a gated community only in spirit.

Lakeview Boulevard E

Lakeview Boulevard E, which originated in David and Louisa Denny’s 1886 East Park Addition to the City of Seattle, is named for its view of Lake Union to the west. For a time part of the Pacific Highway (now routed onto Aurora Avenue N), it begins today at an overpass over Interstate 5 at Eastlake Avenue E and Mercer Street and goes a mile north to Boylston Avenue E and E Newton Street.

Interstate 5 blocks the view of the lake from much of the northern section of the street, but the southern section’s view is still more or less intact.

View of Lake Union, Eastlake, and Wallingford, looking northwest from Lakeview Boulevard overpass at Belmont Avenue E, May 12, 2018. Photograph by Flickr user GabboT, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic

View of Lake Union, Westlake, and Queen Anne looking southwest from Lakeview Boulevard overpass at Belmont Avenue E, May 12, 2018. Photograph by Flickr user GabboT, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Westlake Avenue

Forming a trio with Eastlake Avenue and Northlake Way, Westlake Avenue is so named for running along the western shore of Lake Union. Beginning today at Stewart Street between 5th Avenue and 6th Avenue, just north of McGraw Square, it runs 2½ miles north to 4th Avenue N between Nickerson Street and Florentia Street — the south end of the Fremont Bridge.

Westlake neighborhood and Mount Rainier from the Aurora Bridge, June 23, 2006. Photograph by Flickr user Steve Voght, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Westlake Avenue once started a couple of blocks to the south, at 4th Avenue and Pike Street, and based on the quarter section map, it appears that its former route through Westlake Park between Pike Street and Pine Street is still public right-of-way as opposed to park land. (The portion between Pine Street and Olive Way was vacated in 1986 to make way for the Westlake Center mall, which opened in 1988, and the portion between Olive Way and Stewart Street was closed in 2010 to allow for the expansion of McGraw Square.)

Monorail and streetcar, corner of Westlake Avenue and Olive Way, in 2008. Photograph by Flickr user Oran Viriyincy, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 2.0 Generic Westlake was extended south to 4th and Pike from Denny Way in 1902 (one former mayor has called for that extension to be closed to cars); the original Westlake Avenue (now, properly, Westlake Avenue N) was created in 1895 as part of the Great Renaming ordinance, Section 5 of which reads

That the names of Rollin Street, Lake Union Boulevard and Lake Avenue from Depot Street [changed by the same ordinance to Denny Way] to Florentia Street, be and the same are hereby changed to Westlake Avenue.

Rollin Street, the southernmost portion, was named for Rolland Herschel Denny (1851–1939), the youngest member of the Denny Party at just six weeks old. In its honor, an apartment complex that opened at the corner of Westlake and Denny in 2008 is named Rollin Street Flats.

Rollin Street Flats, northeast corner of Westlake Avenue N and Denny Way, South Lake Union, October 22, 2017. Photograph by Joe Mabel, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International Northlake, Eastlake, Westlake… why no Southlake?

Having covered Northlake, Eastlake, and Westlake so far, one might ask: why is there no Southlake?

There does appear to have been a Southlake Avenue for a time — 1909 to 1924 or so, based on the last mention of it I could find in Seattle newspapers, an article in the August 8, 1924, edition of The Seattle Times on a car crash that had taken place a number of weeks earlier. Now the northern section of Fairview Avenue N, it extended from the intersection of Valley Street northwest to E Galer Street and Eastlake Avenue E, “thus eliminating the present grade on Eastlake for University traffic” in the words of a real estate advertisement in the August 23, 1914, edition of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer. But why the Southlake name disappeared seems clear: once it was decided to extend the Fairview name along the shore lands, there was no other appropriate road to carry it. The northern and eastern shores of Lake Union are just shy of 2 miles long each, but since the lake is shaped like a ? (and, surprisingly, like a uterus if Portage Bay is included) there is hardly any southern shore to speak of — only about ¼ mile.

As for the neighborhood name, I’m not sure why South Lake Union came to be used instead of Southlake. Perhaps it’s as simple as the lack of a similarly named street to “anchor” the neighborhood.

Eastlake Avenue E

Like NE Northlake Way, Eastlake Avenue E is so named because it runs along the shore of Lake Union — in this case, obviously, the eastern one. It, too, was earlier named Lake Avenue (in part), but this was changed as part of the Great Renaming of 1895. Ordinance 4044, Section 6 reads

That the names of Albert Street, Waterton Street, Lake Avenue and Green Street from Depot Street [changed by the same ordinance to Denny Way] to the shore of Lake Union at the northerly point of the Denny–Fuhrman addition, be and the same are hereby changed to Eastlake Avenue.

Today, Eastlake, at 2⁹⁄₁₀ miles in length, extends slightly farther north and south than the roadway mentioned in the ordinance. It starts in the south at the intersection of Court Place and Howell Street as Eastlake Avenue, then becomes Eastlake Avenue E a block north as it crosses Denny Way. From here to just south of E Galer Street it divides the Avenue: E; Street: E section of town from the Avenue: N; Street section. Just north of Portage Bay Place E it crosses Lake Union as the University Bridge, then continues on as the one-way–northbound Eastlake Avenue NE to 11th Avenue NE just north of NE 41st Street. (Southbound, it is fed by Roosevelt Way NE at NE Campus Parkway.)

Eastlake, like Fairview and Boren Avenues, is one of the few north–south streets in Seattle to have three different directional designations.

Looking northeast at the University Bridge from the Ship Canal Bridge, July 2018. Photograph by SounderBruce, Wikimedia Commons, licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International NE Northlake Way

As explained in NE Boat Street, NE Northlake Way was originally Lake Avenue in the 1890 Brooklyn Addition to Seattle, so named because it ran along the northern shore of Lake Union. I couldn’t find an ordinance changing its name from Lake Avenue (used elsewhere, notably for what are now Westlake Avenue and Fremont Avenue N and for part of Eastlake Avenue E) to Northlake Avenue, but the latter name begins to appear in local newspapers in 1901. (Complicating matters slightly, the street appears as North Lake Avenue in the state’s 1907 plat of Lake Union Shore Lands.) Northlake Avenue began being referred to as Northlake Way in 1935, and this was made official in 1956.

Today, NE Northlake Way begins at the west end of NE Pacific Street under the University Bridge at Eastlake Place NE, and continues 1½ miles west to just shy of the Aurora Bridge, where it becomes a private road through formerly industrial land developed by the Fremont Dock Company into a business park. (The Puget Sound Business Journal and The Seattle Times have good articles on how over the years Suzie Burke transformed her father’s Burke Millwork Co., which opened in 1939, into what is today home to local offices for Google and Adobe and corporate headquarters for Tableau and Brooks Sports, among other tenants.) This private roadway continues for ⅖ of a mile beyond the end of the public right-of-way to the intersection of N Canal Street, N 34th Street, and Phinney Avenue N.

NE Northlake Way once began ⅖ of a mile further east, at NE Columbia Road on the University of Washington South Campus, but this stretch was changed to NE Boat Street in 1962, not without some controversy.

Bay Terrace Road

To reach their homes, residents of Bay Terrace — east of Lawtonwood and west of Land’s End at the northern tip of Magnolia — must drive through Discovery Park. Within the park, their street (the narrow neighborhood only has one) is known as Bay Terrace Road, but changes to 42nd Avenue W north of the park boundary. Similarly to Lawtonwood Road, it does not appear to have been officially so designated until 2007, when ordinance 122503 was passed. Also similarly to Lawtonwood Road, it carries no directional designation, since it is a park boulevard.

Bay Terrace Road runs ¼ mile north from Lawtonwood Road just west of 40th Avenue W, and then becomes 42nd Avenue W, which continues on for another ⅕ of a mile to a viewpoint overlooking Shilshole Bay.

Sign for Bay Terrace Road, Discovery Park, October 30, 2011. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff. Copyright © 2011 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved. W Marginal Way SW

W Marginal Way SW, like its twin across the water, E Marginal Way S, began literally as a “marginal way” to “give railroads, street cars and other transportation facilities access to the Duwamish waterway.”

W Marginal Way SW begins at 26th Avenue SW at the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 5. From there, it’s 3 miles southeast to 2nd Avenue SW, by the south end of the 1st Avenue S Bridge. It resumes on the east side of the bridge as W Marginal Way S, an extension of Highland Park Way SW, and runs 4⅖ miles from there to the southern city limits. (For all but the first few blocks of this stretch, it is a limited-access highway carrying Washington State Route 99.) Beyond there it runs 3½ miles more to the vicinity of an interchange with Tukwila International Boulevard. The name is dropped at this point (and does not appear on signs south of the initial few blocks); the highway continues 1¾ miles as Washington State Route 599 to Interstate 5.

Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, 4705 W Marginal Way SW, May 2010. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff, originally appearing in Seattle Then and Now.

Copyright © 2010 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved.W Marginal Way S is the location of the Duwamish Longhouse and Cultural Center, across the street from həʔapus Village Park and Shoreline Habitat (formerly Terminal 107 Park). həʔapus, or x̌əʔapus, was the name of a Duwamish village that was burned down by settlers in 1895. The new longhouse became the first one within city limits in 114 years. Notably, descendants of settlers Charles Terry and David Denny participated in fundraising and advocacy, without which the project would have been impossible, as the Duwamish were forced to purchase back the land. (A good article for more detail is “On the Duwamish River, a longhouse rises,” which appeared in Real Change in March 2009.)

E Marginal Way S

E Marginal Way S and its twin across the Duwamish Waterway, W Marginal Way SW, are good examples of purely descriptive Seattle street names. In fact, they are first mentioned in the press as adjective + noun, not name + type:

- “Marginal ways are urged for both sides of Duwamish waterway.” Seattle Post-Intelligencer, October 27, 1911, in reference to the Bogue Plan

- “Coincident with the completion of the Duwamish waterway and the wide marginal streets on each side, a publicly owned railway should be built along these marginal ways…” C.C. Closson, realtor and the Port of Seattle’s first paid employee, in a letter to the editor, Seattle P-I, July 8, 1912

- “East and west marginal ways, planned by Bogue to parallel the waterway to give railroads, street cars and other transportation facilities access to the Duwamish waterway, will both pass through Oxbow.“ The Seattle Times, March 26, 1914

- “Marginal ways parallel the new waterway for the whole distance, connecting with the main streets of the city running to the south.” Seattle P-I, August 13, 1914

A longer excerpt, from an article in the April 19, 1914, issue of The Seattle Times, explains the reason for their creation:

Second only in importance to the waterway are the projected traffic streets, east and west marginal ways, laid out on both sides of the waterway about 1,000 feet back to give railways and street car lines the opportunity to parallel the waterway on both sides for its entire length, to give service to the industries locating along the waterway. As an allowance of $175,000 was made for East Marginal Way in the $3,000,000 county bond issue for roads, that street is now being condemned by the city and will be constructed 130 feet wide to the south city limits, where it will join a county road. West Marginal Way is also being promoted by interested property owners. As the existing railways are already but a short distance east of the Duwamish River, spurs can be thrown into East Marginal Way at slight expense. Also the port commission is considering a plan for port district terminal tracks on the Marginal Ways to serve the waterway.

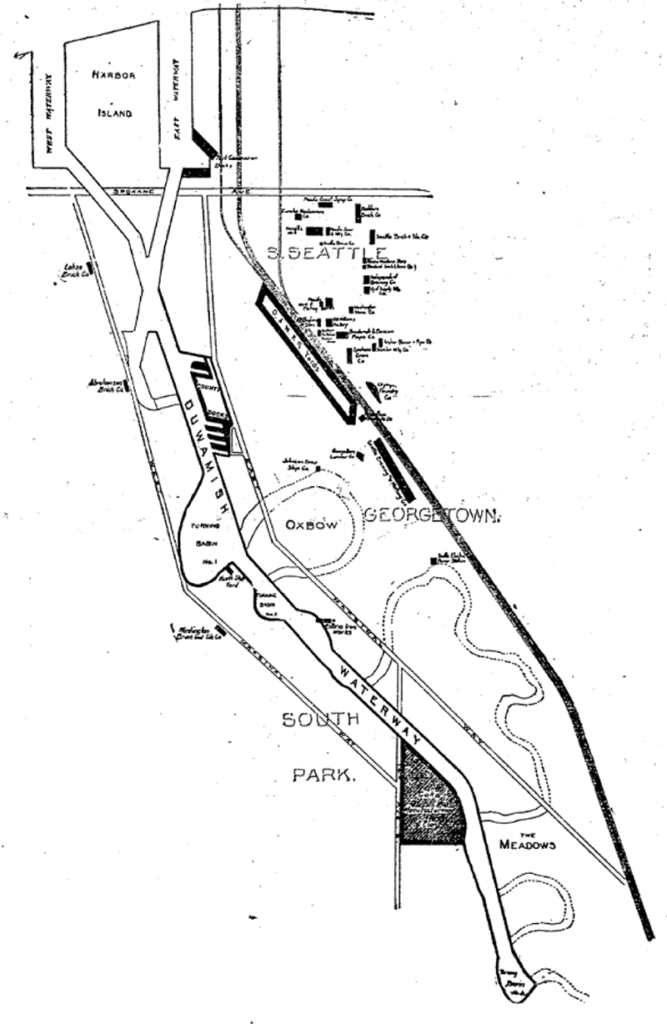

The Duwamish Waterway, whose construction began on October 14, 1913, was a straightening and deepening of the last 6 miles of the formerly meandering river. Construction of the waterway, with Harbor Island at its mouth (the largest artificial island in the world from 1909 to 1938), plus the filling of the Elliott Bay tidelands, are what give Seattle’s harbor its modern shape.

Plan of the Duwamish Waterway, from the August 31, 1913, issue of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, page 44 E Marginal Way S begins as an extension of Alaskan Way S — originally Railroad Avenue, which served much the same function for the central waterfront — at the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 30, and stretches 4⅖ miles from there to the southern city limits. (From the southern end of the Alaskan Freeway to the northern end of the 1st Avenue South Bridge, it carries Washington State Route 99.) Beyond there it runs 3½ miles more to S 133rd Street in Tukwila.

Union Bay Place NE

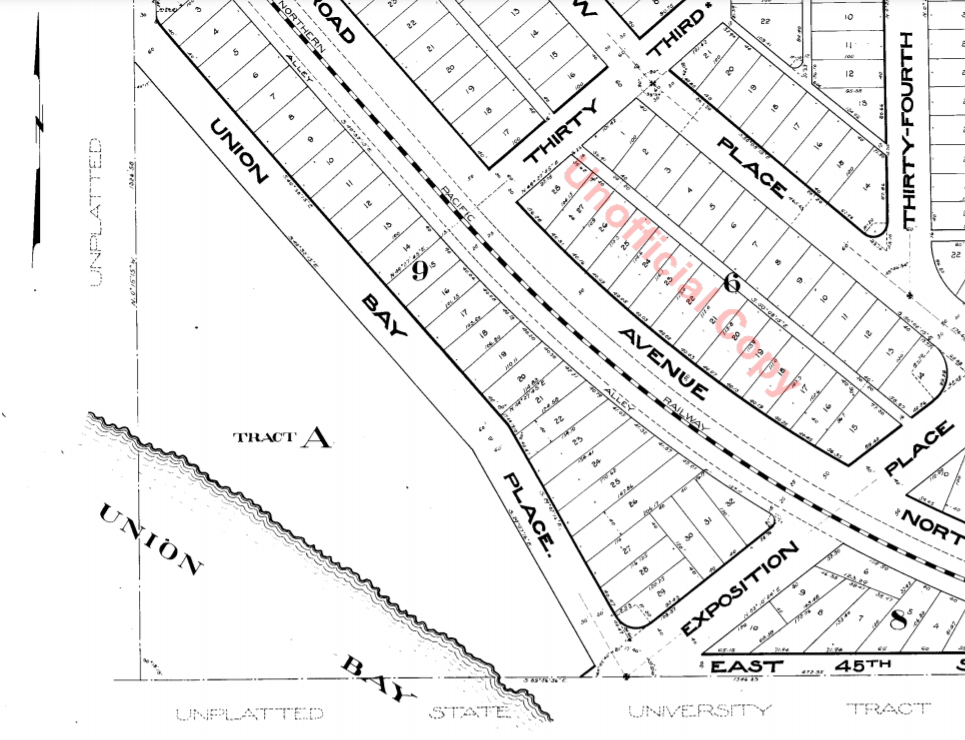

This street, which runs ⅕ of a mile from 30th Avenue NE in the northwest to the “five corners” intersection with NE 45th Street, NE 45th Place, and Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE, was created in 1907 as part of the Exposition Heights addition. Four years later, the street was extended southeast of NE 45th Street through University of Washington property to NE 41st Street. However, in 1995 that portion was renamed Mary Gates Memorial Drive NE.

As can be seen in the map below, it did once parallel Union Bay; however, when the Montlake Cut of the Lake Washington Ship Canal opened in 1916, the lake and bay dropped by 8.8 feet to match the level of Lake Union and this was no longer waterfront property. The southwest corner of this map is now entirely devoted to commercial and residential use.

Portion of plat map of Exposition Heights showing Union Bay and Union Bay Place Union Bay itself was named in 1854 by settler Thomas Mercer, with the idea that it and Lake Union, which he also named, would one day be part of a connection from Lake Washington to Puget Sound. As mentioned above, this did end up happening 62 years later.

Dravus Street

This street was created in 1888 as part of Denny & Hoyt’s Addition to the City of Seattle, Washington Territory by Edward Blewett and his wife, Carrie, of Fremont, Nebraska, who had purchased the land a few months earlier from Arthur Denny and John Hoyt. According to Valarie Bunn in her article “Fremont in Seattle: Street Names and Neighborhood Boundaries,” Edward Corliss Kilbourne may have done much of the actual naming of streets as attorney-in-fact for the Blewetts.

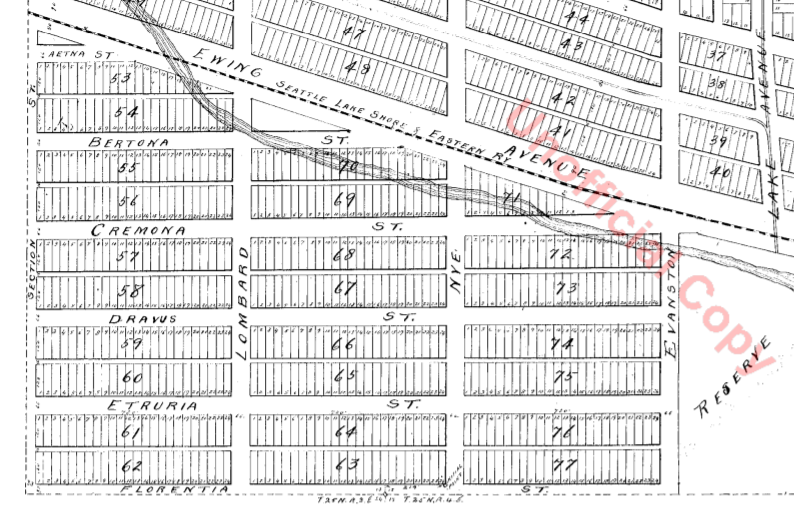

Portion of plat map of Denny and Hoyt’s Addition to the City of Seattle, Washington Territory (1888) showing Aetna, Bertona, Cremona, Dravus, Etruria, and Florentia Streets As can be seen in the plat map above, Dravus is part of a series of streets — Aetna, Bertona, Cremona, Dravus, Etruria, and Florentia — that appear in alphabetical order and have the common theme of being locations in Italy, which had been unified 17 years earlier. I have yet to find a connection between Denny, Hoyt, the Blewetts, or Kilbourne and Italy. The closest I’ve come is an item in the February 28, 1903, issue of The Seattle Mail and Herald, which reports that “on February 27, the Woman’s Century Club met and discussed the subject ‘Italian Art and Literature.’ Mrs. Bessie L. Savage and Mrs. E.C. Kilbourne [Leilla Shorey] prepared papers relating to these subjects.” I would love to find out if there’s anything more solid!

The Drava River, which originates in the Italian region of the South Tyrol, flows from there through Austria, Slovenia, and Croatia, forming much of the border between that country and Hungary, and joining the Danube on the Croatia–Serbia border. It was known as Dravus in Latin and Δράβος in Greek.

Dravus Street begins in the east at Nickerson Street and goes ⅗ of a mile west to 8th Avenue W and Conkling Place W. It resumes for half a block at 10th Avenue W, is briefly a foot path and stairway, and then is an arterial connecting Queen Anne and Magnolia via Interbay, going just over a mile from 11th Avenue W to 30th Avenue W. (This section was originally known as Grand Boulevard, and indeed W Dravus is double the width of the other streets in the area, though it features wide planting strips instead of a central median.) It’s ⅓ of a mile from 31st Avenue W to 36th Avenue W, where it becomes a stairway for a block, and then ½ a mile more from 37th Avenue W to just west of Magnolia Boulevard W, where the roadway ends. (There is a shoreline street end off Perkins Lane W, but it is currently inaccessible.)

S River Street

S River Street is just ½ a mile long, and none of it parallels the Duwamish River. The reason behind this is the same reason S Front Street is perpendicular to the waterway — the rechanneling of the Duwamish River that began in 1913. In Joseph R. McLaughlin’s Water Front Addition to the City of Seattle, filed in 1906, Front Street had a horseshoe shape. North Front Street is today’s Front Street, and South Front Street was changed to River Street in 1907, when West Seattle was annexed to Seattle. The Baist Atlas depiction of the Oxbow, below left, is from 1912, so has the modern name.

Today’s S River Street begins at 7th Avenue S and goes ½ a mile west, ending at 1st Avenue S, below the 1st Avenue S Bridge.

Signs at corner of S River Street and 7th Avenue S, May 22, 2013. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff. Copyright © 2013 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved. S Front Street

Usually, a Front Street designates a city’s waterfront. Front Street in Philadelphia parallels the Delaware River; NW Front Avenue in Portland, Oregon, goes up the Willamette River; Front Street in Toronto runs along Lake Ontario. Seattle once had a prominent Front Street alongside Elliott Bay, but it was renamed 1st Avenue in 1895. The Front Street we do have runs a grand total of ⅖ of a mile split among three segments, and it runs east–west, while the nearby Duwamish River runs north–south. Why is this?

As it turns out, S Front Street — established as part of Joseph R. McLaughlin’s Water Front Addition to the City of Seattle in 1906 — did use to run along the river, before it was rechanneled beginning in 1913. (Here is an excellent post from the Burke Museum on the Duwamish meanders, with some great maps and aerials.) The maps below show its course along the Duwamish River Oxbow in 1912 (left) and its current landlocked state (right). You can still make out its former location, as well as small remnants in the form of the Slip 2 and Slip 3 inlets. (Incidentally, Front Street originally was shaped like a horseshoe — today’s S Front Street was originally North Front Street, and South Front Street is today S River Street.)

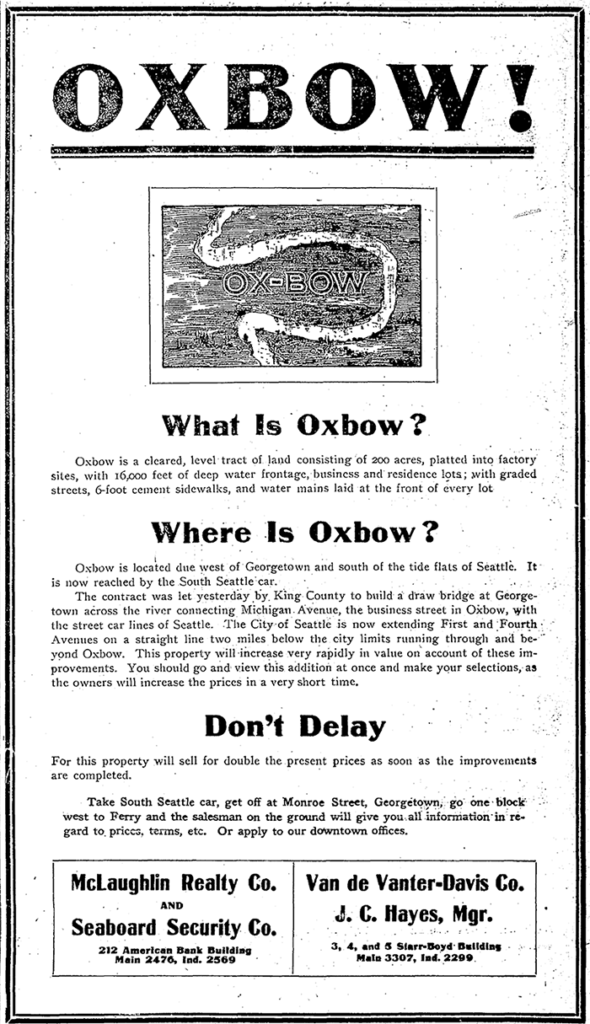

Speaking of the Oxbow, here’s an advertisement for it. So much for that “16,000 feet of deep water frontage.”

Advertisement for Oxbow in June 1, 1906, issue of The Seattle Times Today’s S Front Street begins at 6th Avenue S and goes ¼ of a mile west, ending just beyond 4th Avenue S. There is another 400-foot-long section between E Marginal Way S and 1st Avenue S, below the approach to the 1st Avenue S Bridge. And then there is one last 200-foot-long section on the west side of the Duwamish River — SW Front Street starts at W Marginal Way SW and ends at the entrance to the Port of Seattle’s Terminal 115 (which used to be Boeing Plant 1, the airplane manufacturer’s first production facility).

Incidentally, here’s a great article on the one in New Orleans I came across while looking up various Front Streets. It’s hard to beat a lede like this: “In a city replete with famed streets, scenic avenues and poetic street names, one particular artery excels at being obscure, nominally insipid, marvelously intermittent, and sometimes barely even a street.”

Sign at corner of SW Front Street and W Marginal Way SW, May 20, 2013. Photograph by Benjamin Lukoff. Copyright © 2013 Benjamin Lukoff. All rights reserved. Yukon Avenue S

This very short street (375 feet long) in the Dunlap neighborhood runs from Spear Place S in the south to S Henderson Street in the north. Like Valdez Avenue S, which it intersects, it was established in 1905 as part of Dunlap’s Supplemental to the City of Seattle, and was named after the Yukon River, likely due to the recent Klondike Gold Rush (ended 1899).

Yukon Avenue S, incidentally, holds the distinction of being the at the very end of the list of Seattle streets taken in alphabetical order — hence the tagline for Streets of Seattle, a blog from 2012 that sadly never seems to have gotten off the ground: “Seattle street names, from Adams to Yukon.”

Spring Street

Spring Street was another of Seattle’s “first streets.” Sophie Frye Bass writes in Pig-Tail Days in Old Seattle:

Where springs of clear water bubbled from the earth and the beach was sandy and free from rocks, there the Indians camped. Such a choice spot was Tzee-tzee-lal-litch [dzidzəlalič], which Arthur Denny called Spring Street.

Spring Street begins at Alaskan Way and runs nearly a mile, to Harvard Avenue, before it is interrupted. A few more segments run through the Central District and Madrona. The last is from 38th Avenue to Grand Avenue, at which point it continues to Lake Washington Boulevard as a footpath and stairway.

NW Esplanade

More common in older cities like London (Aldgate, Cheapside, Crosswall, Eastcheap, Houndsditch, Lothbury, Minories, Moorgate, Poultry, Queenhithe, St. Mary Axe, and Walbrook, just to name those that merit a Wikipedia article of their own), single-word street names are a rarity in Seattle. NW Esplanade is one of them. It was platted in 1924 as part of the Golden View Addition, and its extension in 1927 as part of the Loyal Heights Annex.

NW Esplanade runs just over half a mile along the Puget Sound shoreline from Triton Drive NW in the northeast to just shy of the northern boundary of Golden Gardens Park in the southwest. For those who might not know, the word means “a long, open, level area, usually next to a river or large body of water where people may walk.”